What follows here are some stories of those men and women:

The Parkinson family saw a father and three sons serve in the Navy. Two sons, Parky and Clayton, survived the attack on Pearl Harbor where both were on the U.S.S. Oklahoma. Four months later, Parky had what he judged to be “the good fortune” to watch the Doolittle Raiders take off from the Hornet to bomb Tokyo.

Harriet Moore Holmes wore the uniform of a 2nd Lieutenant in the Army Nurse Corps when she arrived at Tripler General Hospital near Honolulu, just one month before the December 7, 1941 attack. Recalling that famous morning decades later, she remembered, “the day went on, with everyone working as hard as they could to save lives and ease the pain of the injured.” Harriet remained at Tripler for the next three and a half years as she cared for America’s wounded from various Pacific island campaigns.

Adolph Kuhn joined the Navy six days after graduating from high school in May of 1940. A Pearl Harbor Survivor, he has written powerful and moving poems about that day, one of which reads in part, “The taste of that oil is still on my lips, That gushed into the harbor from our exploding Ships. Mangled bodies and limbs floating around, As I scrambled for safety to higher ground.” Adolph has also kept a daily diary since January 1, 1939.

Floyd Williams joined the Marines in June of 1940. Two months later the Corps assigned him to the U.S.S. Yorktown as a “seagoing bellhop.” In June of 1942 the Yorktown participated in the Battle of Midway, a turning point in the Pacific war. Forced to abandon his ship after Japanese torpedoes hit it, Floyd survived in the water for about five hours until another ship rescued him. One memory he recalls is how the sailors “wrapped a white Navy blanket” around him in spite of the fact that black oil, from the waters around the Yorktown, covered his body.

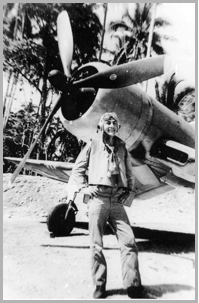

Fred Losch joined the Black Sheep Squadron (VMF 214) as it undertook its second combat tour in November of 1943. As Fred recalls upon hearing of his assignment, “I was thrilled. After just one combat tour under Major Greg Boyington, the Black Sheep were already legends back in the States. Those guys were ‘killers,’ and now I was one of them.” Fred flew thirty-six combat missions with the Sheep, thus becoming part of “the legend.” Read more of Fred's story here.

Sid Zimman fought in the air war as a gunner on a SBD dive-bomber, flying by the end of his tour forty missions. His squadron, VMSB 341, participated in attacks upon Rabaul, the Japanese fortress located on New Britain in the Solomon Islands. As Sid emphasizes, “The emasculation of Rabaul made our later invasions of the Gilbert Islands (Tarawa), Marshall and Mariana Islands less hazardous on our way to Iwo Jima and Okinawa…Although the battle at Rabaul is not well known, because it was never invaded, it was a turning point in the Pacific War…” Read more of Sid's story here.

Don Johnson served on board the destroyer U.S.S. Claxton, part of the “Little Beaver Squadron,” named after a sidekick to Red River, the main character in a comic strip of that same name. Don participated in three major Pacific campaigns--Peleliu, Leyte Gulf, and Okinawa. He witnessed kamikaze attacks in the Philippines and in Okinawa. With the pride of a Navy man, Don points out that in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the Claxton “had the honor of being the first warship back into the Philippines [after American forces were forced to surrender there in the spring of 1942].”

“Iron Mike” Mervosh held every enlisted rank in the Marine Corps, from private to Sergeant Major, in the course of his thirty-five year military career. While he fought in several island campaigns, Mike describes the battle of Iwo Jima as “a perfect battle on a perfect battlefield” and its ferocity led him to conclude that if a Marine “lost a leg, arm, or his eyesight, he came out ahead.”

J.D. Williams, an Army infantryman, was wounded in the last major Pacific battle of World War II, Okinawa. A deeply religious man, he recalls that, “I never had any conflict between my Christianity and my purpose as a soldier…I did not want to go to war, but I was willing to fight to protect my family and my homeland.” Read more of J.D's story here.

Joe and Bea Walsh’s lives have been defined by the core values of faith and family. These fundamental beliefs are rooted in their respective childhood and in their years as young adults during World War II. While they grew up surrounded by a loving family, it was not a complete one for either of them. At an early age, they each lost a parent. Joe’s was a temporary loss, but Bea’s was a permanent one. They shared other experiences, as well. They were both raised as Roman Catholics. This common religious background undoubtedly boded well for their relationship when they first met as adults towards the end of World War II. In that global contest, they each served in the military, Joe in the Pacific and Bea stateside. On December 7, 1941, Joe’s Marine Corps defense battalion was temporarily based in Hawaii. He thus fought in America’s opening battle of World War II--the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor. Like Joe, Bea also served as a Marine in World War II. Her duty station was at Brown Field in Quantico, Virginia. There Bea worked in a women’s aviation unit, specifically in Assembly and Repair. For both Joe and Bea, faith and family came to take on new meanings during World War II. Click here to read the Introduction to their story. Read more of the Walsh's story here.

Neal Hook, at the age of ninety, wrote a memoir on his WW II Army service. He entered the military early in 1943. Assigned to the 31st Infantry Division, Neal’s unit trained in the States for a year before it shipped out to the South Pacific in the spring of 1944. Although he clearly remembers his many months in combat, Neal admits that he no longer recalls specific dates. This is understandable. What Neal does remember, however, speaks to the powerful hold war memories can have on veterans. It takes courage to revisit such moments. One is struck by the honesty with which Neal shares some of his memories. At one point early in his combat experiences, he admits “I wasn’t scared. I was terrified.” When a good friend was killed, Neal characterizes himself as “devastated and demoralized,” even though, as he points out, “we expected to lose many men.” After the war, Neal became a teacher. Now, decades following his retirement, he continues to share lessons with those who are interested in the history of WW II, especially from the perspective of soldiers who fought in it. Neal’s body still carries the shrapnel scars from the war. And his mind still holds vivid memories of his time as an Army rifleman. This is Neal’s story, as he wrote it.

Durrell Conner's character was largely defined by his beliefs in God and in country. He drew on both throughout his life, especially during World War II. On one of the most consequential mornings in United States history, after a devastating, two-hour enemy attack, Yeoman 2nd Class Conner raised the Stars and Stripes on the battleship USS California. The date was December 7, 1941. Durrell knew that the country, like the flag, would rise again. When the war ended, he recognized God's hand in the Allied victory. Read more of Durrell's story here.

George Coburn - United States Navy fire controlman first class George Coburn wrote his mother a letter on November 19, 1941. At the time, he served on the battleship USS Oklahoma, moored at Pearl Harbor. In the letter, George complained of “the monotony” he felt described life on board the ship. “Today is the uninteresting duplicate of yesterday, tomorrow will be the duplicate of today, and so on into what seems infinity, but I guess it can't last forever. Something is bound to happen.” Less than three weeks later, on December 7th, Japan attacked the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. Congressional declarations of war followed. With the Oklahoma severely damaged, the Navy transferred George to the heavy cruiser USS Louisville. As a member of its gunnery division, he participated in several Pacific campaigns. This is the story of a sailor who fought on the frontlines of history from the first hours of America's entry into World War II through its last major battle at Okinawa. Read George's story here.