We suggest another lens through which to view the history of December 7, 1941. Focus on the actions of the Pearl Harbor Defenders, members of the United States military who engaged the enemy during the Japanese aerial attack. They came to be called “Pearl Harbor Survivors,” men now in their nineties and some even older than that. Looking at them today, one might understandably see these veterans as “survivors,” in more than one way. Try to imagine them, however, as soldiers, sailors, and Marines in their late teens or early twenties. On that December day, men who could do so reported to their duty stations or fought where they stood for almost two hours.

The word "Survivors" emphasizes what was done to them (the men survived the Japanese attack). The word "Defenders" calls attention to what they did -- they engaged the enemy.

On Ford Island, sailors belt ammunition to be used by machine guns

Sandbags and guns on Ford Island create an antiaircraft emplacement.

Ground fire from Pearl Harbor Defenders hit a Japanese Zero fighter. The enemy plane had fired its machine guns in a strafing attack over Hickam Field. Note the smoke trail in the sky.

While the Japanese targeted Wheeler Field, an Army airbase, their battle plans ignored an Army landing strip sixteen miles away--Haleiwa Field. It was not much of a military installation, with only one unpaved runway. Haleiwa had been used for aerial gunnery practice, which is why ten planes sat on the field, temporarily assigned there. Most were from the 47th Pursuit Squadron.

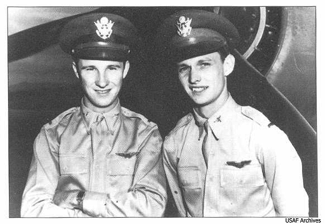

Two of those pilots, Lieutenants Kenneth M. Taylor and George S. Welch, were at Wheeler Field’s Officers’ Club when the Japanese planes appeared in the sky over Pearl Harbor. Acting on their own initiative, Taylor and Welch called Haleiwa Field. They ordered the squadron’s ground crew to arm their P-40 fighters and prepare them for takeoff. The two pilots then drove to Haleiwa, reportedly at a speed of one hundred miles an hour. Immediately after their arrival, the lieutenants took off to engage the enemy in the air. They did so over Marine Corps Air Station Ewa Mooring Mast, where Taylor and Welch experienced combat for the first time. Together, they shot down six Japanese planes that morning.

The primary target of enemy planes on December 7th was a line of vessels off of Ford Island in the center of Pearl Harbor--Battleship Row. On board the USS California was Chief Radioman Thomas J. Reeves. The hash marks on the left sleeve of his white jacket gave evidence of his long Navy career that had begun in 1917, just months after the United States entered World War I. It is probably not an exaggeration to invoke the judgment, “The Navy was his life.” The chief oversaw a ninety-man radio division, respected by everyone who knew him. On December 7th, torpedoes struck the California, resulting in fire and smoke that filled the ship. The main radio room on the third deck could no longer function. Reeves helped his men get to the upper deck. There he saw how critically the antiaircraft guns needed ammunition. The attack had destroyed a mechanized hoist that could have brought the ammo up to the main deck. Reeves thus went back down to the third deck to arrange a manual transfer of the ammo from below to above. While it was flooding, fire was also moving through the lower deck. Nevertheless, the chief organized sailors to bring the ammo up by hand. At one point, Reeves collapsed from the smoke and flames. It is believed he died less than fifty feet from the radio compartment that had been his unchallenged domain. Chief Reeves was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Over at the Marine Barracks, located on the grounds of the Navy Yard, Marines went into action. When the Japanese attack began just minutes before 8:00 a.m., Major Harold C. Roberts of the 3d Defense Battalion was at his home in Honolulu. He quickly drove back to his unit, arriving at the barracks around 8:20 a.m. as the second wave of enemy planes started to drop their bombs. The major established his command post at the southern corner of the parade grounds. From there, he issued several orders. With their guns in need of more ammunition, Roberts approved a plan to send Marines to two ammo dumps located outside the Navy Yard with the hope that one man could return with more ammunition. He set up a fire control system in the middle of the parade grounds; eight Marines acted as spotters, using field glasses to get a sighting on the enemy planes for battalion guns. What they saw was communicated to some buglers who then used their instruments as an alert system. One blast from the instruments, for example, meant planes had been spotted coming in from the north. Two blasts signaled an enemy approach from the east. Roberts also ordered groups of about sixteen riflemen each to sit on the ground near each other; an officer or NCO directed their combined fire at the Japanese planes.

One of the Marines in Roberts’ defense battalion was then-Private First Class Joe Walsh. As a 1943 military record of Joe’s reads, his service up to that point included his “participation in [the] defense of Pearl Harbor.” In the decades after the war, Joe’s good friend and fellow Marine Jim Evans preferred to be identified as a “Pearl Harbor Defender” rather than a “Pearl Harbor Survivor.” We agree with Jim. This section of our web site honors the military men and women who served on the front line in the first hours of America’s entry into World War II. Some were able to engage the enemy on December 7, 1941. Caught by surprise, it did not take long for soldiers, sailors, and Marines who could do so to react as they had been trained to do, even though battle conditions did not favor them. Understand that for the majority of service personnel, December 7th represented their initiation into combat. We recall their actions and their fighting spirit when we “Remember Pearl Harbor.”

U.S. government poster,

c. 1942-1943

The First Pearl Harbor Day: During WW II, Americans paused each December 7th to “Remember Pearl Harbor.” They called the day itself “Pearl Harbor Day.” Read how one small town--Winchendon, Massachusetts--observed the first Pearl Harbor Day in December 1942.

Radio reports reached the continental United States while Japanese planes were still dropping their bombs upon American ships and installations. Read about when and how “the Home Front” first learned of the enemy attack at Pearl Harbor.

One December 8, 1941 newspaper carried the names of thirteen men in the United States military who died at Pearl Harbor. This was just one day after the attack. Read who those thirteen men were and read examples of how newspapers headlined the story out of Hawaii.

USMC Private First Class Joe Walsh was a member of a defense battalion temporarily stationed at Pearl Harbor, awaiting orders to ship out. Read how he and other Marines in his unit responded to the attack. (Background to Joe can be found on the Pacific Theater section of this web site under an entry on Joe and his wife Bea Walsh; it explains Joe’s enlistment as well as his service up to and after Pearl Harbor.]

USMC Corporal Ted Roosvall, Jr. wrote his father soon after the attack. A Chicago-area newspaper published part of the letter. Read about Ted and the story the paper printed.

Jud McDannold served as a radioman on an Admiral’s staff in December 1941. Read a story about Jud and read, too, his firsthand account of what he remembered years later about the enemy attack.

Patrol was a weekly paper published “on board the U.S. Submarine Base” at Pearl Harbor. The issues were, as Patrol announced, written “in the interest of Submarine Squadron Four and the Navy.” Pearl Harbor Defender Durrell Conner kept the March 14, 1942 edition all these years. Read Patrol’s “An Open Letter” addressed to the Axis Powers from “Uncle Sam’s Boys.”

Seaman 1st Class James E. Mason was a radioman on the USS Oglala. Read his account of December 7, 1941 and an accompanying story on Jim and his ship.

Yeoman 2nd class Durrell Conner served onboard the battleship USS California as a member of the Admiral’s coding board. As Durrell explains, “My job was to encode and decode all of his classified messages.” Soon after the enemy attack ended, Durrell raised the United States flag on the California. Read his firsthand account of that morning. Durrell's full-length story is in the Pacific Theater section.

Louise Milke Moats Whatley, the wife of a civilian who worked for the military, experienced the Japanese attack firsthand. She and her husband “Scoop” lived, in Louise’s words, “about two blocks from Hickam Field,” the Army air base adjacent to Pearl Harbor. Two days after enemy planes appeared in the sky over Oahu, Louise wrote her family in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Her letter focused on the morning of December 7th and its immediate aftermath. As Louise explained, “we are right in the midst of all of it.” She vividly described the enemy attack. Read Louise’s December 9th letter and the Dec 10th telegram she sent her family. Examine the envelope, front and back, which carried the December 9th letter from Hawaii to Iowa; note how long it took for the letter to go that distance. (Martial Law had been declared in Hawaii on December 7, 1941. Censorship began immediately. The stamp “released by I.C.B” on the back of Louise’s envelope indicates that censors have read the letter and allowed it to leave the island. “I.C.B.” stands for the “Information Control Branch.”) And lastly, see Louise herself in two different photographs.

United States Navy fire controlman first class George Coburn wrote his mother a letter on November 19, 1941. At the time, he served on the battleship USS Oklahoma, moored at Pearl Harbor. In the letter, George complained of “the monotony” he felt described life on board the ship. “Today is the uninteresting duplicate of yesterday, tomorrow will be the duplicate of today, and so on into what seems infinity, but I guess it can't last forever. Something is bound to happen.” Less than three weeks later, on December 7th, Japan attacked the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. Read George's account of that morning placed in a historical context. George's full-length story is in the Pacific Theater section.

Five cemeteries in San Diego County became the final resting place for eleven of the servicemen killed on December 7, 1941. They were officers as well as enlisted men. Two were newlyweds. Some had fathers who had been or were serving in the U.S. Navy. Others, in their childhood, had lost their mother or father. One sailor was part of a trio of brothers assigned to the same battleship. A few were sons of immigrants. More than one of them had been born during the First World War, only to be killed in action during the opening hours of the Second World War. One received the Medal of Honor posthumously, another the Navy Cross posthumously. Each December 7th, we should pause to remember the 2,403 servicemen who died in defense of Pearl Harbor. At least eleven are buried in San Diego County. A twelfth, a resident of Fallbrook, is interred in an Orange County cemetery. Years after the war ended, Pearl Harbor Defenders who lived through December 7, 1941 founded a national organization, the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association. One of its mission statements read, “To shield from neglect the graves, past and future, of those who served at Pearl Harbor on such day.” Servicemembers who survived the attack are no longer alive to carry out that sacred trust. Younger generations must assume the responsibility. Read a brief profile of some Defenders, buried in San Diego County, and how they died on December 7th.

Robert (“Bob”) Tyce was one of 68 civilians killed in the attack at Pearl Harbor. He was born in Czestochowa, Poland in 1903. At age two, his family immigrated to the United States. As a chemical engineer, Bob's father found professional work in one city after another. Their trip across the Atlantic proved to be only the first of many movements ever westward. The Tyces did not “stay put” until several years after their arrival when California's San Diego County became their home. Bob and a brother lived there in the 1920s. They settled in the city of Chula Vista. The two learned how to fly and founded an aviation school to teach others to do the same. An airport bore their family name. A sense of adventure seemed to be part of the Tyce DNA. Bob, though, made one more move. In 1935, he relocated to Hawaii. Bob started another aviation company in Honolulu that taught students to fly; the company also flew passengers around the islands. On the morning of December 7, 1941, Bob stood on the tarmac of a private airport in Honolulu. Machine gun fire from a Japanese plane killed him. Because of the circumstances of his death, he was one of the first civilians to die that day, if not the first. Read about Bob Tyce's adventuresome life that ended when he became part of one of the most well-known days in United States history.

William Jeremiah Powell served on board the USS Curtiss, a seaplane tender. He would be one of twenty crewmen killed on December 7, 1941. William enlisted in February 1940. The Navy trained him as a mess attendant because William was a Black sailor. At that time, Navy regulations did not allow Blacks to be assigned to any other area. But William certainly could have done more than work in the mess. It appears he graduated from high school, as did all nine of his siblings. William was born and raised, as generations of his family before him had, in Gates County, North Carolina. His great-grandparents on both sides apparently were enslaved. Just a few generations after emancipation, descendants acquired their own land that they owned free and clear. Still, legally sanctioned racial discrimination surrounded them. William lived in such a world, even in the U.S. Navy. Because of his race, he was limited in another way aside from his everyday duty station. The Command on his ship assigned him a battle station, but it would not have been one where he fired a machine gun at enemy aircraft. Black sailors simply were not to do that. They might help load the guns, but they were not to fire them. Yet that is probably exactly what William did on December 7th. He lost his life because of that action, one for which he has never been fully recognized. Read William's story here.

George Whiteman, Andrew Walczynski, and Jerome Szematowicz shared more than their status as members of the Army Air Corps. All three grew up in small-town America--George in Sedalia, Missouri; Andrew in Duluth, Minnesota; and Jerome in Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania. Additionally, like most Americans, they did not come from well-off families. They were from the working class; two fathers labored as coal miners and a railroad yard employed the third father. The three soldiers, too, represented both “old-stock” Americans and new Americans, as did the nation. The lineage of only one, George Whiteman, can be traced back to early 19th century America. Jerome Szematowicz was the son of early 20th century immigrants, while Andrew Walczynski himself had come to the United States at that same time as a child. Significantly, all three soldiers graduated from high school. Their high school degree set them apart from most of their working class peers. The degree undoubtedly factored into their assignment to the Army Air Corps. On December 7, 1941, each was at his airbase on the island of Oahu--Second Lieutenant Whitman at Bellows Field, Staff Sergeant Walczynski at Wheeler Field, and Private First Class Szematowicz at Hickam Field. Read their stories here.